30th JAMCO Online International Symposium

February 2022 - March 2022

For a Sustainable World – Responses to the COVID-19 Crisis

The Possibilities and Issues arising from an Experience of Remote Collaboration in a Teacher Training Project:

Games on Sustainable Development Goals developed between Teachers of a Private High School and University Students

This paper is about an online training program for teachers of a privately run high school. Specifically, it had the teachers and university students collaborating remotely to devise teaching materials in the form of games about sustainable development goals (SDGs). The objective here is to shed light on: (1) what the participants learned; and (2) how this can be put into practice in day-to-day classes.

The online training program (hereinafter referred to as the project) was put together by the Yakushima Ohzora High School on Yakushima Island and two of the authors (Konno and Kishi), whose field of expertise is educational technology. Training programs aimed at improving lesson design are held on a regular basis at the local and prefectural level for teachers in the publicly run senior secondary schools. For those in the privately run senior secondary schools, however, they are nearly always conducted by the schools themselves, or else in the form of workshops (open to those wishing to participate in them) provided by the Japan Institute for Private Education (Nippon Shigaku Kyōiku Kenkyūsho) (2021). The Yakushima Ohzora High School viewed this project as an independent program.

Changes to the curriculum guidelines for schools laid down by Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology have put greater emphasis on lessons centered on inquiry. It is vital, first of all, for teachers to have experience of inquiry themselves if this is to be put into practice in the classroom. Yakushima Ohzora High School conducted this project to give teachers experience of this kind of learning and to have them thinking about the processes it involves, so that they would be able to guide their pupils in inquiry-based learning.

The project took place online over a four-day period in March 2021. Yakushima Ohzora High School is on Kagoshima Prefecture’s Yakushima Island, which has some of the richest natural surroundings in Japan. When these surroundings are harnessed as a teaching resource, there is a close affinity with sustainable development goals, which were made the subject for inquiry-based learning. This type of learning assumes various guises, such as the testing of hypotheses, fieldwork, study of the available literature, proposing solutions for problems, and creating things. But the setting of tasks and the gathering of information, organizing and analyzing it, summing it up and giving expression to it, are processes common to all of them. This project was a quest to create something, where the objective was to come up with games to foster understanding about SDGs.

The following section uses a theoretical framework of learning and development to describe the project’s intent. Section 3 gives an account of how the games were developed and describes what was produced. Section 4 uses the reflections of the teacher who took part in the project to illustrate the possibilities and issues with remote collaboration in teacher training. The final section will consider the prospects and issues for the future.

2. The Quest to Devise Games

Two factors were behind this project to devise games for inquiry-based learning.

The first is that experience of developing games, play in other words, is conductive to learning that involves dialogue, creation, imagination, and collaboration, all of which are valued in inquiry-based learning. Play has been a field of academic interest for more than a century. It has had key role in theories about development, education, and therapy, and in understanding history, anthropology, social conventions, and art (Gordon 2012). Although play is to a degree supported by intuitive concepts of it being a pleasurable action, no clear definition for it exists. Moreover, the research on play has centered on early childhood development; it has had little to say about adults. Lois Holzman at this juncture expanded on Lev Vygotsky’s concepts about play to put forward theoretical and practical arguments that play-based development can be observed not only among children, but adults also (Holzman 2014). Holzman regards play as a human activity usually involving dialogue, creation, imagination, and collaboration. In this project, the play was to come up with games, which had the participants engaged in dialogue with others of different strengths and talents to set tasks, and had them collaborating to gather, organize and analyze information, thereby deepening their understanding about what was to be done, and at the same time picturing in their minds who would be using the games they intended to develop. This was regarded as a salutary process; the activities were giving the participants a taste of inquiry-based learning.

The second factor is that the project gave the teachers experience of developing teaching materials that embody a whole range of different perspectives. When teachers put together, not only games, but the likes of education programs and lessons, it is a process of analysis, design, development, implementation, and evaluation (Suzuki 2002). As we mentioned earlier, the teachers at privately run senior secondary schools in Japan have limited opportunities to participate in teacher training programs, which makes it difficult to create education programs incorporating views from outside the schools. The objective of this project was to come up with teaching materials in collaboration with university students. The situation, as it were, was that they could only be devised with the involvement of outsiders. But the amount of influence wielded by the outsiders was very much restricted, the reason being that the input was coming from university students who were similar in age to the teachers’ own pupils. Furthermore, the students were not on the island, so the collaboration presented a situation that required the teachers to tell the outsiders in Tokyo about the resources and attractions of Yakushima, which was inevitably an opportunity for them to reappraise and rediscover a whole range of things about the island. This is how they got a taste of inquiry with various other people. This in turn gave them experience of the possibilities and issues that are involved in the belief that this ought to prove useful when the teachers actually came to guide their pupils in inquiry.

3. The Project in Practice

The project had twenty-three participants: ten teachers at the Yakushima Ohzora High School; and thirteen students from two universities in Tokyo. Yakushima Ohzora is a senior secondary school that educates pupils by correspondence outside the framework of the normal classroom. It wanted a program that would give teachers experience of inquiry-based learning and also get them thinking about the processes involved, so they could subsequently guide pupils in such learning. Two of the authors (Konno and Kishi) were asked to put together an online program according to these aims. This project to devise games on sustainable development goals, involving university students to achieve its aims, got underway in March 2021.

Table 1 shows how the project was conducted. On day one, Konno and Kishi gave a summary of the project and its aims. In order to familiarize the participants with its significance, this was followed by a talk about two topics: play and learning; and class design in line with sustainable development goals and theories about teaching materials. Moreover, two existing card games were mentioned, and the participants as a whole shared their views about how they could be harnessed in education. The teachers and university students were subsequently organized into four groups to come up with games. Incidentally, when they were online, the participants displayed and only called one another by their first names so as not to make them conscious of their positions of teacher or university student.

From day two, each group pursued its activities in the times and manner of its own choosing, given that the participating teachers and students had their own matters to attend to, such as school work or part-time jobs. The only proviso was that the finished games be announced on day four.

On day four, each group gave a 30-minute presentation on what it achieved, and there was discussion on how the games could be improved upon in terms of suitability and relevance.

Table1: How the Project was pursued

| Day | Activity |

|---|---|

| Day 1 |

|

| Day 2 | Each group engaged in creating a game |

| Day 3 | Ditto |

| Day 4 | Each group showed what it produced; question and answer session |

*The activities were pursued between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. each day

3. 1 Theory for the Development of Teaching Materials, Focus on SDGs

The talk on day one about theory for the creation of teaching materials described the development processes shown in Table 2 that draw on Katsuaki Suzuki’s theory of class design (Suzuki 2002). It ascertained that the four-day project would work to stage (4)

Table2: Theory for the Development of Teaching Materials

| Process | Tasks involved |

|---|---|

| (1) Picturing the materials |

|

| (2) Picturing the creation | Plan, do, see |

| (3) Clarify the entry and exit points | Set learning goals by spelling out a course of action and evaluation and passing criteria |

| (4) Visualizing the structure | Start from the exit and work back to the entry point |

| (5) Creating the materials | Prepare materials in accordance with the guiding strategies |

| (6) Conduct a formative assessment | Find out where improvements can be made |

| (7) Improving the materials | Make improvements in accordance with the formative assessment |

(Suzuki 2002)

Furthermore, the talk about sustainable development goals in classes set out their nature and what they should be like, in that one ought to be able to perceive links. Specifically, in each stage of the creation process, the criterion was to blend links into the games: links between oneself and others; between oneself and the community; between Japan and the world; and between oneself and the world. The idea was that these links would get individuals to consider themselves as global citizens and global issues as matters relevant to themselves, which is what the sustainable development goals set out to do.

3. 2 What the Participants Came up with

The participants were organized into separate groups on day one. Table 3 gives a summary of the games they came up with. The groups relied on cloud computing for production and for organizing their ideas. Photographs 1-3 give an idea of what the groups did.

Table 3: Games Devised by the Groups

| No | Name of game | Objectives | Rules |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yakushima Island Board Game |

|

The players roll the dice to visit tourist spots on the board, seeing how much of the island they can cover in a three-night, four-day stay. The players get to think about how they can enjoy the island, and also help preserve its environment. The idea is to promote both fun tourism and eco-tourism. |

| 2 | Welcome on a Journey to Yakushima! |

|

The focus is on foods. The players roll the dice to advance along the board. Points are earned by living on the island and engaging in small games. Players get to solve incidents occurring on the island. This game about Yakushima involves lateral thinking. |

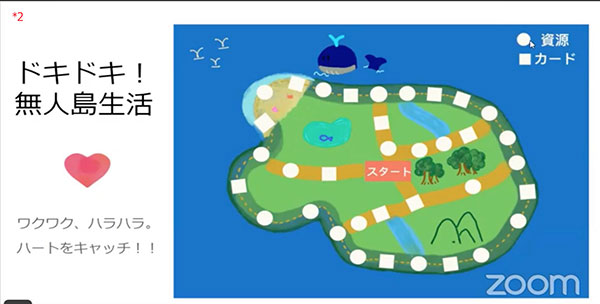

| 3 | Living on an Uninhabited Island! |

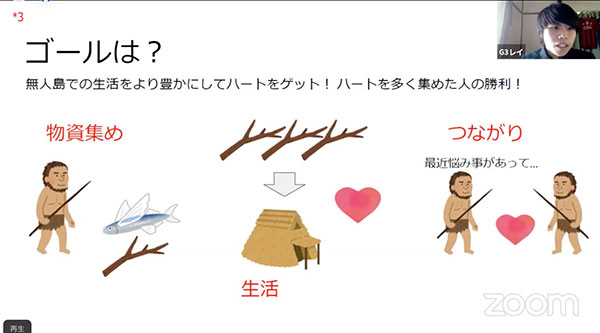

|

Players roll the dice to advance along the board. They gather heart tokens when they make life better in some way on an uninhabited island. The players explore the island sharing the excitement and tension of the things happening there. |

| 4 | Where are You Going? What are You Doing? |

|

Game gives the players certain tools to come up with the best ways enjoying themselves on the island. Players try to earn the greatest number of fun points. |

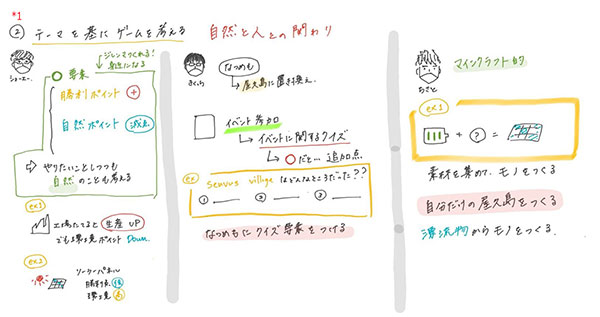

Photograph 1. Using cloud computing to bring ideas into view and into fruition

Five participants share their ideas

*1 Subject for game: Human involvement with nature

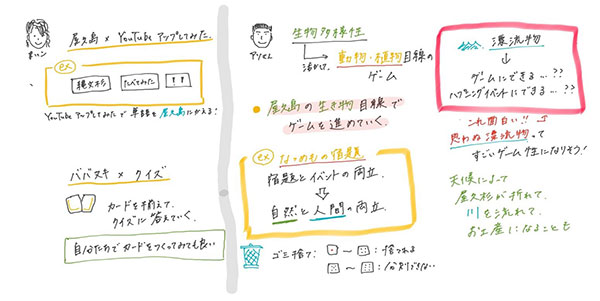

Photograph 2 Shaping Ideas into a Game

*2 Living on an Uninhabited Island! Collect heart tokens!

*3 Pick up a heart token every time you help make life better on the island. The player who gets the most tokens is the winner.

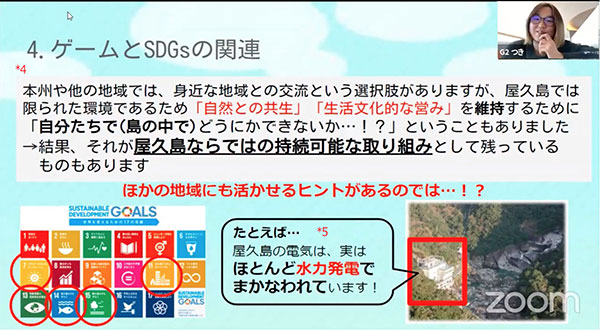

Photograph 3 Explaining how the Games relate to SDGs

*4 Although Honshu and other parts of Japan have the option of pursuing links with nearby communities, what do you do in a small place like Yakushima? How do you exist with nature and maintain your livelihoods? There are sustainable initiatives out there that the island can offer.

*5 Other communities can do this too! Hint . . . Yakushima Island actually gets most of its electricity through hydropower!

4. Possibilities and Issues with Remote Collaboration in Teacher Training

There was a questionnaire for the teachers to express their views freely, which provided data to shed light on the objectives of this paper: (1) what the participants learned; and (2) how that can be used in practice in day-to-day classes. Table 4 gives details about the nine of the teachers who took part in the project. (Two of them are in administrative positions.)

Table 4: Details about the Participating Teachers

| Teacher | Years of teaching experience | Teaching subject |

|---|---|---|

| Teacher A | 1 | Japanese |

| Teacher B | 1 | English |

| Teacher C | 1 | Science |

| Teacher D | 3 | History, geography, civics |

| Teacher E | 3 | Mathematics |

| Teacher F | 4 | Japanese |

| Teacher G | 5 | English |

| Administrator A | 11 | Health & physical education |

| Administrator B | 13 | Science |

4. 1 Gathering and Analyzing the Data

The nine teachers were asked to fill in the questionnaire in July 2021. They were not required to give their names. The following questions were asked:

- (1) Did you learn anything from this project?

- (2) Did you feel that this remote collaboration changed you in any way?

- (3) Has this experience prompted you to focus on sustainable development goals in your classes?

- (4) Would you be willing to participate in any remote collaboration in the future?

The teachers were asked to give their views freely in the first three questions. The final question only required them to give a yes or no.

The replies given to questions (1), (2), and (3) were taken apart and the similar comments were categorized under headings. This resulted in three categories.

4. 2 Findings

Here are the traits for the three categories and excerpts of the teachers’ responses.

(1) Collaboration among people of different ages and ways of bringing together thoughts and ideas

Just about all of the teacher training programs conducted to date have been restricted to fellow teachers and have provided almost no opportunities for involvement with people from different backgrounds. The teachers were working with university students who were younger than they were, which put them into contact with other values and perspectives.

Furthermore, information was shared via cloud computing, which helped bring the participants’ ideas into the open. The teachers were aware of the importance of having a place where they could express their own views. The non-face-to-face setting allowed for this.

| Excerpt of responses under the category: Collaboration among people of different ages and ways of bringing together thoughts and ideas |

|---|

|

(2) A sense of achievement which is necessary for self-improvement

The teachers gained new perspectives from this project, which gave them experience of collaborating remotely and of taking part in a quest to come up with games that could be used as teaching materials. The experience gave them an intuitive understanding of the relevance and significance, and a mental picture of how these things could be incorporated into their lessons. They got a sense of achievement, as it were, which is necessary for any self-improvement.

| Excerpt of answers under the category: A sense of achievement which is necessary for elf-improvement |

|---|

|

(3) Getting a grasp of SDGs when bringing them to classes

Even a single experience of putting newly acquired knowledge into actual practice can make all the difference. Sustainable development goals are a broad concept, and the teachers at this school until then did not have any pictures in their own minds as to how they might be incorporated into their lessons. In other words, although they were aware of the concept, it did not directly concern them. The project turned SDGs into something that was personally relevant, prompting them to change their behavior so they might take the next step.

| Excerpt of answers under the category: Getting a grasp of SDGs when bringing them to classes |

|---|

|

4. 3 Consideration of the Possibilities and Issues in Teacher Training

This section will consider the possibilities and issues in teacher training programs from the findings of this project. We will begin with the possibilities and describe three intervening factors that separate the inner and outer worlds. The key terms are setting, colleagues, and time. We will then touch on two issues in teacher training.

- (1) Possibilities in teacher training: The three intervening factors that separate the inner and outer worlds

The Covid-19 pandemic is accelerating the use of information and communications technologies, which includes the establishment of online learning environments. This has enabled schools to link up faster and more readily with people, organizations, and so forth in the outside world. The environment has been transformed for students and teachers alike. This means greater possibilities in teacher training, of which this project is an example. The possibilities, as it were, lie within the greater space that now exists with the outside world rather than within the inner world of the school.

The setting provided a link with the outside world. There the teachers spent their time differently from what they were accustomed to. They got experience of working together with university students, the kind of people they normally do not associate with. They were members of a team that was creating a game that could be used for teaching purposes.

Fresh surprises and impressions beckoned from this domain that the teachers had not ventured into before. There they had time, as it were, to indulge their intellectual curiosity and be unexpectedly inspired.

This project, in other words, had the teachers pursuing activities within a setting different from their normal work. The colleagues they were working with were the kind of people they normally do not encounter. And there was time to perceive a different set of feelings. It can be argued that these three intervening factors – setting, colleagues, time – were a source of stimulus for the inner world, where time can tend to be monotonous and devoid of any quirks. An environment, as it were, that lets teachers have fun learning in the outside world is filled with possibilities, and there are all kinds of possibilities for fostering personal development as well. - (2) Issues for Teacher Training

The issues with teacher training are twofold. The first is understanding the objectives. The existing programs of the conventional mold are not too difficult to imagine. The participants feel as if the training does not directly concern them; they are there because they had been ordered by their principal or head teacher, or because they always take part in a certain program at a certain time every year. Quite a few of the participants would be unable to give a clear answer if asked, “Well, why are you here?” This suggests avenues for grappling with the question of improving training programs. Why? Because all of the teachers answered in the affirmative when asked: Did you learn anything from this project? At all stages prior, during, and after the project, there were opportunities to establish why the teachers were taking part in it. They were given a clear understanding of the objectives beforehand, and this was reaffirmed while the project was in progress. Afterwards in their day-to-day work, they got to look back on what they had put into the project, which we believe ought to be conductive to the drawing up of any follow-up action plans.

The second issue is ensuring two-way interaction. It is easy to imagine the programs that pass down knowledge where the participants all too focused on receiving it from their instructors, which unconsciously makes it a passive exercise. A clear-cut division between the two sides creates a one-way flow of information from instructor to recipient, hampering any kind of environment, as it were, that will allow for active involvement from the latter. This is can happen regardless of whether the training is being done face-to-face or online. We believe, in the first place, that there ought to be a format providing for an interactive flow between the instructor and the recipients or among the latter, rather than just a one-way flow of knowledge from the former. An online program, for example, would require a setup to enable collaboration via cloud computing, or else a discussion among a small number of people via a teleconference allowing for a verbal and visual exchange among the participants. Any face-to-face programs would likewise require a setup based on an interactive flow among the participants. The need for such environments was raised in the responses we saw in section 4.2.

The objective of this paper has been to shed light on: (1) what the participants learned; and (2) how this can be put into practice in day-to-day classes.

- (1) What the Teachers Learned

Coming up with teaching materials in the form of games gave the teachers a taste of inquiry, which we can say is what they learned in this project. It was a process where the participants were colleagues without any superior or subordinate roles, in which tasks were set through dialogue with others, each with their respective strengths. They collaborated to gather, organize, and analyze information so as to get a better understanding of what they had to do, and were able to picture in their minds the games they wanted to create and who would be using them. Setting tasks and the gathering, organizing, analyzing, summing up and expressing of information are the processes for inquiry-based learning. Having play as the subject of these processes removed the usual constraints of training programs that pass knowledge from instructor to participants, and those for producing teaching materials, human relations, and suchlike, which it can be argued was a key factor in fostering collaboration and free-thinking among the participants. - (2) Putting What was Learned into Practice in Regular Classes

The project was able to give the teachers experience of creating teaching materials that embodied a range of perspectives from an understanding of sustainable development goals and collaboration with other people. From this they perceived that SDGs are relevant to their own lives, and not just those of others, and they embraced them in their day-to-day classes as we saw in the comment: “In our lessons, the pupils are spending more time thinking about the seventeen SDGs.”

The formats and subjects of training programs are issues for the future. Holding face-to-face programs is difficult in the current circumstances, and online programs are likely to be adopted if this persists. But even then, they will require an interactive environment.

The setting of subjects need not be a quest for immediate results in teaching; they can be of little direct relevance to teachers’ classes or be areas that interest teachers. We believe if teachers get fun out of learning something, this will flow into their classes as a matter of course, even if the programs are not directly connected to lessons or the running of classes or schools.

- Burghardt, Gordon. “Defining and Recognizing Play.” Peter Nathan and Anthony D. Pellegrini (Eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Development of Play. Oxford University Press, 2012. pp. 9-18.

- Holzman, Lois. Vygotsky at Work and Play. Trans. into Japanese by Yūji Moro as Asobu Vygotsky: Seisei no Shinrigaku e. Tokyo: Shinyosha, 2014.

- Japan Institute for Private Education (Nippon Shigaku Kyōiku Kenkyūsho). 2021

https://www.shigaku.or.jp/ (accessed 29 October 2021) - JAPAN SDGs Action Platform. 2019.

https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/gaiko/oda/sdgs/about/ (accessed 29 October 2021) - Suzuki, Katsuaki. Kyōzai Sekkei Manual (A manual for designing teaching materials). Kyoto: Kitaohji Shobo, 2002.

Note:

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 19K02984

Ryōhei KIKUCHI (Yakushima Ohzora High School)

Takayuki KONNO (Meisei University)

Makiko KISHI (Meiji University)

Ryōhei KIKUCHI

Appointed Head Teacher of the Yakushima Ohzora High School (run by KTC Gakuen) in April 2019; assumed the post of Vice-Principal in April 2021.

Takayuki KONNO

Associate Professor, School of Education, Meisei University

Specialist in educational technology (class studies and teacher education). Received honorable mention in the 34th Japan Society for Educational Technology Awards in 2019. Works with educational institutions, non-profit organizations, and non-government organizations in Japan and developing countries to conduct research on class studies and training programs for teachers to improve the quality of their lessons and to enable them to collaborate with others. Author of Shutaiteki-taiwatekide Fukai Manabi no Kankyō to ICT Active Learning ni yoru Shishitsu-Nōryoku no Ikusei (The unsupervised, interactive deep learning environment and using information and communications technologies and active learning for fostering competency and capabilities) (Toshindo, 2018).

Makiko KISHI

Associate Professor, School of Global Japanese Studies, Meiji University.

Field of expertise: educational technology. Pursues research on education and learning environments for diversity and inclusion. Has focused on the comprehensive learning periods and other exploratory learning in Japanese schools. Outside of Japan, has focused on the Middle East (Syria, Palestine, Turkey), studying the design stages where anyone, including the children of refugees and other socially disadvantaged children, can perform beyond who they are and mutually develop with their diversity, in terms of their personalities, experiences, strengths, and so on.

Return to 30th JAMCO Online International Symposium contents page

Return to 30th JAMCO Online International Symposium contents page