29th JAMCO Online International Symposium

February 2021 - March 2021

The Potential of Broadcasting and New Media for Supporting Education During the Coronavirus Pandemic

The COVID-19 Transformation in Higher Education

~ Online Learning in Hawaii, the United States, and the Pacific Islands ~

Abstract

In modern times, U.S. higher education has never been impacted by local and national incidents such as weather-related disasters, earthquakes, shootings, national protests, terror incidents, and global epidemics. The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 changed everything. This paper describes how universities and colleges in Hawaii and the United States transformed instructional delivery as the virus seriously affected local and national economies, healthcare workers, and the welfare of families. The author will describe changes that occurred in education and the possible benefit to teaching and learning that may emerge in the future.

Introduction

On August 30, more than five months after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a COVID-19 pandemic, the New York Times reported that more than 6 million Americans were infected by the coronavirus (The New York Times, 2020a).

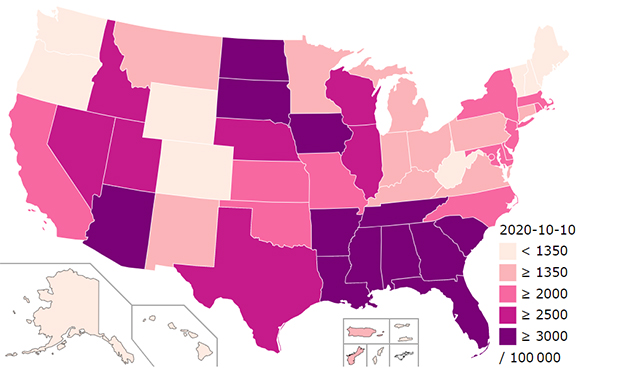

Six weeks later, as of October 10, the number of positive COVID-19 cases in America reported by the John Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center was 7,709,628, with 214,305 reported related deaths (John Hopkins University, 2020). Worldwide, 37 million cases were reported with the United States leading all countries followed by 7 million in India and 5 million in Brazil. In America, the largest per capita increases (Figure 1) were located within the Southern and Mountain states (Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, North & South Dakota). The United States saw a spike in cases after the Memorial Day (May 26) and Independence Day (July 4) national holidays, presumably from people gathering at recreational spots (lakes, beaches, and public and theme parks) without wearing masks and practicing social distancing. As of this writing, America is facing a third peak in the number of reported cases.

American life has changed as in virtually all other countries globally. Crowd oriented gathering places and events have been cancelled. Millions are without jobs and struggling to afford housing. Schools and colleges have limited the number of face-to-face or in-person classes this fall. More than 26,000 cases were linked to universities starting classes in August and September (CONAHEC, n.d.).

The New York Times Editorial Board (2020) stated that the United States continues to experience a lack of leadership and incompetence from the national government for failing to contain the spread of COVID-19. This may have resulted in more than 100,000 Americans unnecessary deaths (Riodan, 2020).

Figure 1. Confirmed cases of COVID-19 per 100,000 residents in the USA by state or territory

Souce:Wikimedia Commons. User: Ythlev

The Impact of COVID-19 in America

United States Economy

On July 31, the World Economic Forum (Mutikani, 2020) described the changes in the economy during the pandemic:

- The COVID-19 caused the biggest impact to the U.S. economy since the Great Depression.

- The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) fell at a 32.9% annualized rate, the deepest decline since records were first kept in 1947.

- 30.2 million Americans were receiving unemployment checks in the week ending July 11.

On June 8, 2020, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), an independent, nonprofit research group, officially declared that the U.S. economy entered a recession in February 2020 (Congressional Research Service, 2020b). On July 31, the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) released estimates that the economy, as measured by GDP, contracted at an annual rate of 32.9% in the second quarter of 2020 compared to the preceding quarter. In other words, if this decline were to continue for one year, the economy would have decreased by one-third compared to the first quarter.

The second-quarter 2020 decline was driven by COVID-19, which caused widespread disruptions to supply (production) and suppressed private demand (spending). However, BEA stated the precise effects of COVID-19 on GDP could not be explained.

United States Unemployment

The U.S. Congressional Research Service (2020c) in an updated October 2020 report, Unemployment Rates During the COVID-19 Pandemic: In Brief, stated:

- The unemployment rate peaked in an unmatched way, not observed since data was first collected in 1948, in April (14.7%) before declining to a still-high level in September (7.9%).

- In April, every State and the District of Columbia reached unemployment rates greater than their highest unemployment rates during the Great Recession.

- Unemployment is concentrated in industries that provide in-person services. Significantly, the leisure and hospitality industry experienced an unemployment rate of 39.3% in April, before declining to 19.0% in September.

A Brookings Institute report added that the pandemic has been particularly damaging for small businesses, which represent the majority of businesses in the United States and employ nearly half of all private sector workers (Bauer et al., 2020).

In July, 2.3 million workers were unemployed due to permanent layoff, which was 11.8 percent of those either unemployed or employed and not at work. By February 2021, 4.5 million individuals will have been unemployed for more than 26 weeks, and almost 2 million will have been unemployed for more than 11 months. Long-term unemployment can lead to lower future earnings and less likely to own a home.

Further, disruptions in child care have caused many working parents to drop out of the labor force, a development that (without significant policy changes) could have long-lasting negative effects on labor market outcomes for years to come.

A recent Pew Research Center survey (Parker et al., 2020) found that, one-in-four adults could not pay their bills since the outbreak began, one-third had used their savings or retirement accounts to make ends meet. About one-in-six or 17 percent borrowed money from friends or family or received food from a food bank.

Black Americans, Hispanics, lower income and those without a college degree were the hardest hit economically. Nearly half of U.S. adults with lower incomes had trouble paying their bills, rents or mortgages since the start of the pandemic.

A Brookings Institution report (Bauer et al., 2020), mentions that levels of food insecurity and of very low food security among households with children increased during the pandemic. Food insecurity occurs when a household does not have sufficient food for its members to keep healthy and active lives and lacks the means to obtain more food. Very low food security is the same as hunger and indicates whether there is a significant or consistent disruption in food consumption.

The renowned Mayo Clinic reported (Marshall III, 2020) that in the United States racial and ethnic minorities are unequally affected by the coronavirus. Recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), shows that non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native people were 5.3 times more likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19 compared to non-Hispanic white people. Among non-Hispanic Black people and Hispanic or Latino people, they were about 4.7 times the hospitalization rate of non-Hispanic white people.

In the U.S., nearly 25% of employed Hispanic and Black or African Americans work in the service industry, compared with 16% of non-Hispanic white workers. Many are employed as nurses or practitioners in the healthcare industry. Others are employed as essential workers. American ethnic and racial minorities are living with underlying health conditions and may be more likely to reside in multi-generational homes, crowded conditions, and in densely populated areas, such as New York City. Social distancing is more difficult and hence the possibility of infection transmission is greater.

Pacific Islanders

As of Friday, August 14, one-third of confirmed COVID-19 cases in Hawaii were non-Hawaiian Pacific Islanders — including but not limited to Marshallese, Samoans, Tongans, Chuukese and other Indigenous peoples of the Pacific — even though they make up just 4% of the state’s population (Hofschneider, 2020).

The current situation was predictable: Pacific Islanders in Hawaii are more likely to work in low-wage jobs, live in crowded households, lack health insurance and suffer from diabetes and other diseases that are associated with worse COVID-19 outcomes.

Pacific Island Nations

In contrast, Pacific Island nations have responded to the spread of the pandemic by quickly closing their borders to international travelers being alert to any possible transmission of the virus. As of October 10, the WHO reported zero infections for American Samoa, Samoa, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Palau, Tonga, Vanuatu, and other Pacific Island nations (World Health Organization, n.d.)

The author’s colleagues from American Samoa (R. Turituri, W. Thompson & L. Laolagi, personal communication, August, 2020) reported that the island nation closed its borders in March, very early in the pandemic. Arrivals require approval from the Governor and the COVID-19 Task force. Upon approval, a 14-day quarantine is required for travelers to meet criteria set forth by the Department of Health.

The government of American Samoa has actively kept its citizens informed about the coronavirus (Office of the Governor, 2020) and has established guidelines and conducted teacher training on how to prepare and conduct classes. Fall classes began in late August. High school students attend classes in-person on a Monday-Wednesday (grades 9 and 10) or Tuesday-Thursday (grades 11 and 12) schedule. Online classes are held in Zoom when students are not in school. On Fridays, school personnel clean and sanitize classrooms and facilities used by students while teachers use it for planning purposes. Students are ensured that online access is available from home.

U.S. higher education

Historically, higher education in the United States has never been disrupted nationally by incidents such as extreme weather, earthquakes, shootings, national protests, terror incidents, and global epidemics (SARS, Ebola, HIV, etc.). The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 did and it changed everything.

In higher education, universities quickly changed to online learning. On March 6, the University of Washington became the first major university to cancel in-person classes and exams. By the middle of March, colleges across the country followed and more than 1,100 colleges and universities in all 50 states cancelled in-person classes or switched to online-only instruction while spring graduation ceremonies were cancelled or postponed (Smalley, 2020). The main focus of higher education institutions is continuing through the fall semester. There is much uncertainty about the pandemic. Campus reopening plans varied a lot from one university to another. However, they generally fell into three categories:

- Planning for in-person instruction with social distancing

- Creating a hybrid model or limiting on-campus student numbers

- Moving to online-only instruction

The University of Hawaiʻi

On March 12, 2020, Dr. David Lassner, President of the University of Hawai‘i declared that all classes will be transitioned to online learning immediately after the annual spring break, starting on March 23 (UH News, 2020a). In-person courses were scheduled to resume Monday, April 13, in the hope that faculty and students could return to normal classroom practices. In fact, in-person classes never resumed. The University completed its spring semester online.

The University maintains updated information about COVID-19 that applies systemwide to all 10 campuses that include a research campus (UH-Mānoa), two baccalaureate campuses (West Oahu College, Maui College) and seven community colleges (Kapiʻolani, Leeward, Honolulu, Windward, Kauaʻi, Hilo and Hawai‘i-Pālamanui) (UH News, 2020d). Additionally, each campus, such as the main Mānoa campus provides guidelines for faculty, staff and students (University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, 2020).

In July, President Lassner reported to the Board of Regents that 54% of scheduled Fall 2020 classes will be held online, 23% in hybrid modality and 23% in person. (President’s July 2020 highlights and updates) All intercollegiate sporting events were suspended indefinitely by agreement of the presidents and chancellors of the institutions in their respective athletic conferences.

However, due to a sudden increase in confirmed Covid cases in August, the President announced on August 10 to limit student in-person class activity unless absolutely where it was required, such as in art, dance or technical trades (Lassner, 2020). These classes would be held in strict compliance with coronavirus health and safety guidelines and best practices. University employees were instructed to work from home (UH News, 2020b). Since then the Mountain West Conference (American football) has scheduled a reduced schedule of intercollegiate football games beginning in November.

Recently, the University of Hawai‘i announced that the fall 2020 semester enrollment had increased at UH-Mānoa, its main research campus, by 3.1%, while decreasing by 3.2% overall. However, the community colleagues showed a slight increase for underserved communities, an important target population in spite of a slight decline.

Overall, UH enrollment declined 0.8%, from fall 2019 which was the smallest overall decline since 2012 when enrollment was near record high levels (UH News, 2020e).

This news was greeted favorably as some thought that this was due to the reluctance of Hawaii residents to enroll in or return to mainland universities because of the coronavirus spread among campuses having reopened for the fall semester. The cause of these enrollment changes are currently being further studied.

Online Teaching and Learning. The University of Hawai‘i Online Innovation Center (UHOIC) created the Remote Instruction During an Emergency website (UH Online Innovation Center, n.d.) to assist during this transition. This website includes a Teaching During an Emergency Checklist for Faculty. Individual campuses alerted faculty to additional resources and training opportunities, and they could have requested more assistance upon completing an online request assistance form.

Students who do not have access to their own computers could use those available in campus libraries and computer labs. UHOIC and UH Information Technology Services has worked with campus offices and others to ensure support for students and faculty with other specific needs.

Faculty support for delivering online instructions is provided by instructional development professionals through ICT (voice, video, email) or by scheduling in-person appointments. Such support is available throughout the system. Likewise, internet resources were presented to students about online learning (University of Hawai‘i, n.d.). This included information and guidance related to communications, learning tools, internet access and receiving help. For example, students were encouraged to create a “successful and structured learning environment” that is quiet, scheduled, and having the expectation that it will take as much, or more time, to engage in an online course.

Computers were available for student use at campus libraries and computer labs (with social distancing protocols in place). At the Kapi‘olani campus, for example, students could borrow loaner computers from the Library for their own use at home.

Non-profit professional educational associations focused on teaching and learning, such as EDUCAUSE in higher education, and The International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE), focused on K-12 educators, quickly assembled resources for their members to make adjustments to teaching online. EDUCAUSE maintains a resource webpage, COVID-19 (EDUCAUSE, n.d.), while ISTE makes resources available through its news organization EdSurge (n.d.).

Fall 2020 Campus Openings

As the fall semester arrived, numerous campuses had to close or limit student movement on campus. The New York Times reported in September (Hubler & Hartocollis, 2020) that after opening for a few weeks, university campuses in the US became coronavirus hot spots with hundreds of new confirmed cases, similar to meat packing plants and nursing homes earlier in the pandemic.

The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, for instance, imposed a lockdown. The University of Nebraska-Lincoln, even as the university suspended several fraternities and sororities for parties, cases continued to increase. The State University of New York at Oneonta sent students home after the coronavirus spun out of control on campus in less than two weeks, with more than 500 cases. The University of Alabama randomly tested three percent of the campus population weekly and penalized more than 600 students for violating a ban to gather together on or off campus. The University suspended 33 students.

As of October 8, a New York Times survey of over 1,700 American colleges and universities confirmed more than 178,000 coronavirus cases. (New York Times, 2020b)

One university president was quoted as saying, “Maybe everything will have to remain virtual until we have a vaccine.” This circumstance is very challenging, indeed.

In contrast, by carefully assessing the spread of the virus in Hawaii, monitoring government action, working together with campus administrators, department heads, staff and faculty, and establishing guidelines based on scientific information and best practices, the University of Hawai‘i has reported only 40 total confirmed coronavirus cases among students and employees throughout its entire system since April 2, 2020. Only seven cases were reported in the 14 days prior to October 12. In contrast to mainland residential universities, however, UH is primarily a commuter university, with a limited number of students residing in dormitories. Furthermore, UH has had a long history of e-learning beginning with two-way interactive television between campuses and education centers since 1990 (Fleming & Hiple, 1999).

The University of Hawaiʻi also requires the use of a health check-in app, Lumisight (iOS & Android), an easy and convenient method for individuals to conduct a daily check of their health status prior to going onto any UH campus or off-campus facility (UH News, 2020c).

Transition to online classes

As thousands of university campuses and countless school districts have transitioned to online learning, a few key questions begs to be answered: How successful is online learning and how can it be improved when there is more time to prepare?

Fortunately, the unplanned transition to online instruction has seen some success among university students. In a recent Longevity Project and Morning Consult poll, 33% of respondents said that they were “very satisfied” in their online college classes. Another 43% said they were “somewhat satisfied”— which are relatively positive for something hastily put together in a few days. Terri Cullen, a professor at Oklahoma University’s College of Education, said that once teachers “began to think outside the traditional time,” they took advantage of unique features of online learning (Stern, 2020).

Some faculty members, on the other hand, have struggled with the technology and with the fact that what works in person does not always translate online. And some students have struggled similarly. Eleven percent of respondents to the Longevity Project poll said that technical issues were the biggest challenge they faced, and a large group of 38% reported that their biggest challenge was staying focused and on track with assignments.

Loss of revenue and enrollment

The American Council on Education, in a letter to congressional leaders (Mitchell, 2020) pleaded for additional financial assistance to offset lower revenues of universities and colleges. Fall enrollments are lower as many students cannot afford university tuition. Universities are unable to benefit from other services such as dining and student housing. The number of international students, who pay a higher tuition, has decreased significantly as travel from many countries have been restricted. New charges have also been incurred relating to coronavirus testing, contact tracing, quarantine, and learning technologies.

According to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, early indications are college enrollment is lower across the USA. Overall, post-secondary enrollment is down 1.8% compared with last year, and community colleges see the biggest drop – a decline of 8%, according to data reported as of September 10 (Schnell, 2020).

U.S. Government Support

The CARES Act established a $31 billion Education Stabilization Fund consisting of a Governor’s Emergency Relief Fund, an Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund, and a Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund. The Governor’s Emergency Relief Fund provides $3.0 billion to governors to provide emergency funds to local educational agencies, higher education institutions serving students within the state, and other related organizations for a wide range of purposes including complying with national laws, social and emotional support, and maintaining education related jobs. The Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund provides for distributing $14 billion to address needs directly related to coronavirus, including adjusting courses to distance learning and granting student aid for tuition, food, housing, health care, and child care (Congressional Research Service, 2020a).

Lesson Learned

COVID-19 pushed universities, their employees and students, into adopting online learning on a massive scale. Additional from the 2020 spring semester and more importantly, from the fall semester will reveal the success of this pivot.

Preliminary indications are that this was possible, and may have a potential to continue over the long haul. Among those engaged in online instruction, the belief is that online learning classes will improve as both faculty and students adapt and become accustomed to this mode of instruction. Practitioners of online instruction also believe that the reputation of online learning will rise.

The University of Hawai‘i Office of the Vice President for Community Colleges (OVPCC, 2020) administered surveys to faculty and students at the end of the Spring 2020 term. 46% or 389 of the total faculty employed and 1,411 students responded to the survey, representing 6% of total number of students.

The responses show that COVID-19 disruption created difficulties for students and faculty personally. Reliable internet and a space to work or study were commonly cited across the various campuses. Additionally, over half of students and more than 70% of faculty were worried about their health and safety for the coming fall semester. Students commented how a well-designed online course and regular communication with faculty helped them to complete courses. Comments showed the need for faculty to respond to student questions promptly. Some indicated that the use of scheduled meetings delivered through video conferencing apps such as Zoom were very helpful. This option was preferred by 2 to 1 over asynchronous (only) online classes. In other words, a hybrid delivery model (online and off-line) appears to be more effective for student learning.

Faculty reported a drop in student participation after Spring Break when the move to online instruction occurred. In spite of this, a majority of faculty (65%) reported that students achieved learning outcomes at a similar or better rate than previous semesters.

This brief summary does not describe everything about the COVID-19 online pivot among community college students and faculty. However, it does show that online learning can produce positive student outcomes. However, faculty training and development, along with adequate internet access and appropriate tools and learning resources are important in achieving positive outcomes.

Over the past two decades, researchers have published data comparing online learning to classroom (in person, or face-to-face) learning. As reported in the 2013 review, only a few studies employed rigorous research methods. However, of those that did, the findings indicate that students do as well in online or hybrid courses as they do in face-to-face on in-person versions of the same course (Kurzweil, 2015). Given the current conditions and in the face of COVID-19, the author, among others, thinks that it is more productive to discuss how online learning may be as effective or better than traditional classroom learning and what teaching strategies and learning tools could be used to attain such results.

Opportunity to innovate

The author, who has engaged in faculty support and taught online learning classes since 1995, is convinced that the pandemic has created a huge opportunity to innovate learning—to research and gather valuable data on how to enable effective online learning practices including strategies for student engagement and tools to help students learn. Results are already starting to emerge. Within a year or two, we anticipate that best practices will emerge from the pandemic pivot to online learning.

Looking ahead

Participants at the TCC 2020@25 Online Conference (https://2020.tcconlineconference.org/) provided the following data in response to an evaluation survey item about how the pandemic affected their work and what will happen to online teaching and learning AFTER the pandemic ends. The TCC Online Conference, targeted to educators primarily in higher education and held annually for 25 years, emphasizes the use of educational technologies in distance learning and emerging technologies for teaching, learning and creativity. As a 25th anniversary feature, a global series of plenary sessions called “One Day in the Life of TCC,” was presented during the entire 24 hours on April 15 with presenters from Spain, Finland, France, England, Canada, the USA, Egypt, South America, Hawaii, Japan and Korea (TCC Hawaii, 2020).

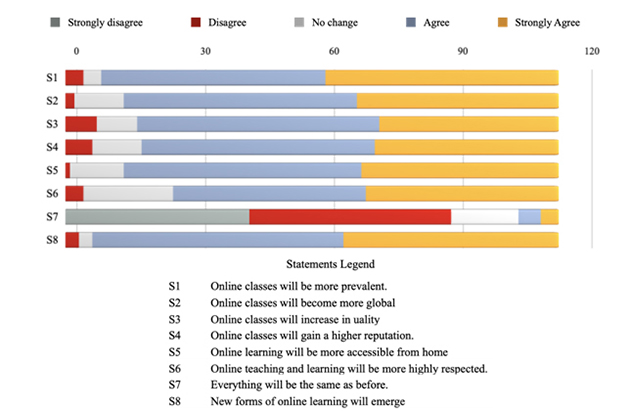

Figure2. TCC 2020@25 Responses to COVID-19 Survey Items

As the event was held during the initial months of COVID-19, statements were presented to participants as part of its usual conference evaluation questionnaire (Figure 2). 110 respondents to the questionnaire overwhelmingly agreed that the coronavirus pandemic will change the nature of online teaching and learning. Online classes will be more prevalent, more global, increase in quality, become more reputable, more accessible from home, gain respect and new forms of learning may emerge. The participants were emphatic that teaching and learning will no longer be the same (Figure 2, S7). Professor Aydin from Anadolu University, Turkey (Torigoe, 2020) and Professor Suzuki (2020) from Kumamoto University, Japan, while presenting plenary sessions, mentioned how an elementary school and a national academic conference respectively, quickly pivoted toward online delivery.

Web 2.0

Since Web 2.0 or the read-write web was popularized by Tim O’Reilly (2005) applications are no longer boxed, generally less expensive and quickly deployed in large numbers of users. Such a rapid change in technology was brought about by users owning the smartphone and a resulting proliferation of apps through online app stores. The world wide web (WWW) shifted from a static (read only) to a dynamic (read-and-write) platform where available information changes in real-time.

Mobile devices

In February 2019, the Pew Research Center reported (Silver, 2019) that more than five billion people used mobile devices, and over half were smartphones. A median of 76% among 18 advanced economies surveyed had smartphones. Only six percent were without. In Korea, 100% have mobile phones, whereas in the U.S., 94% and in Japan 92% owned mobile phones respectively. Even among emerging economies, a significant majority owned mobile phones (78%) although the number of smartphone users were less.

With certainty, based on the success of Android and iOS smartphone platforms,, this number continues to rise. The author anticipates that as mobile device (smartphones and tablets) adoption increases worldwide, online learning will shift from being web-based and become more compatible with mobile device form factors. Today, many more applications are suitable for viewing on mobile devices than just a few years ago.

Learning tools

Faculty have implemented the use of a wide variety of mobile and web compatible applications in the classroom. Zoom and Google Meet are available free or minimal costs for online meetings and real-time instruction. A variety of learning management systems such as Canvas, Big Blue Button and Moodle are available for educators to deliver content asynchronously. Collaborative tools such as Jamboard, Google Drive, and Padlet are simple to use while providing features for multiple users to engage in a single document. Others such as Flip grid and Padlet facilitate asynchronous learning, whereas Socratic and Mentimeter are useful for interactive class meetings and synchronous online events. Jane Hart (2020) has compiled a list of tools for learning based on an annual survey of educators for 14 years.

Digital divide

In 2018, 24% of rural adults say access to high-speed internet is a major problem in their local community, according to a Pew Research Center survey (Parker et al., 2018)). In other instances, the cost of internet service is not affordable to many residents. A 2017 report states that in the US, more than 60 million urban Americans don’t have access to or can’t afford broadband internet despite much higher connectivity rates in rural areas (Molla, 2017).

The Brookings Institution, a highly reputable public policy research NPO says that the internet is no longer “nice to have,” it is critical. It is a fourth lifeline utility in addition to water, gas and electricity. Whether working and studying from home or applying for unemployment compensation, the internet has kept activities alive (Wheeler, 2020).

Given the differences among emerging economies compared to economically advanced nations, there is a need for public and private interests to provide internet access to all. Even in the United States, in rural or remote areas, there are areas where students cannot access instruction online. Generally, this action is left for government agencies.

There is some progress, however. The Pewʻs Trust Magazine report (Winslow, 2019), America’s Digital Divide, indicated that policymakers in rural and urban states are creating new ways, including partnering between public and private entities and using grants from foundations to bring broadband internet to sparsely populated places. Small providers are emerging along the coast of Maine, rural Indiana, and in North Carolina.

Experts and two consumer advocate NPOs have disagreed with the latest Federal Communications Report saying that the data presented was flawed and that action is needed to address the digital divide (Consumer Reports, 2020; Taglang, 2020). Unfortunately, this divide still exists and the United States government has yet to take action to narrow this digital divide.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted teaching and learning at all levels as educators had to pivot to online learning in spring 2020. The evidence is slowly emerging that this effort has been met with success with the cooperation and collaboration among administrators, faculty, support professionals and students. In the author’s view, this is a grand experiment that will eventually result in better practices for online learning. Online learning will occur globally, and in some instances, become the main mode of learning. The reputation of online learning will increase and it may be taken for granted in the years ahead. Online (ubiquitous) teaching and learning will improve significantly and become a feature of our daily lives.

References

- Bauer, L., Broady, K., Edelberg, W., & J. O’Donnell. (2020, September 17). Ten facts about COVID-19 and the U.S. economy. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/ten-facts-about-covid-19-and-the-u-s-economy/

- CONAHEC. (n.d.). Here are the latest college coronavirus updates. https://conahec.org/news/more-25000-cases-us-campuses-here-are-latest-college-coronavirus-updates

- Congressional Research Service. (2020a, July 8). CARES Act Higher Education Provisions. CRS Reports. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11497

- Congressional Research Service. (2020b, August 10). Understanding the second-quarter fall in GDP. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11478

- Congressional Research Service. (2020c, October 2). Unemployment rates during the COVID-19 pandemic: In brief. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46554

- Consumer Reports and Access Now call for FCC to expand broadband access in response to COVID-19 crisis. (2020, May 14). Consumer Reports. https://advocacy.consumerreports.org/press_release/consumer-reports-and-access-now-call-for-fcc-to-expand-broadband-access-in-response-to-covid-19-crisis/

- COVID-19. (n.d.). EDUCAUSE. https://library.educause.edu/topics/information-technology-management-and-leadership/covid-19

- The Editorial Board. (2020, September 09). Mr. Trump knew it was deadly and airborne. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/09/opinion/trump-bob-woodward-coronavirus.html

- EdSurge. (n.d.). Coronavirus. EdSurge. https://www.edsurge.com/news/topics/coronavirus

- Fleming, S., & Hiple, D. (1999). ITV in Hawai`i: the Hawai`i Interactive Television System (HITS). Foreign Languages on ITV. http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/sfleming/flitv/4.htm

- Hart, J. (2020, September 1). Top 200 tools for learning. Top Tools for Learning 2020. https://www.toptools4learning.com/

- Hofschneider, A. (2020, August 17). Health officials knew COVID-19 would hit Pacific Islanders hard. The state still fell short. Civil Beat. https://www.civilbeat.org/2020/08/health-officials-knew-covid-19-would-hit-pacific-islanders-hard-the-state-still-fell-short/

- Hubler, S., & Hartocollis, A. (2020, September 11). How colleges became the new Covid hot spots. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/11/us/college-campus-outbreak-covid.html

- John Hopkins University. (2020, October 10). COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE). https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

- Kurzweil, M. (2015, March 11). The most recent studies of online learning still find no significant difference.

- Ithaka S+R. https://sr.ithaka.org/blog/the-most-recent-studies-of-online-learning-still-find-no-significant-difference/

- Lassner, D. (2020, August 10). UH reduces presence on campuses as COVID-19 impacts increase in Hawaiʻi. University of Hawai‘i News. https://www.hawaii.edu/news/2020/08/10/reduced-presence-on-campuses/

- Marshall III, W. (2020, August 13). Coronavirus infection by race: What’s behind the health disparities? Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/expert-answers/coronavirus-infection-by-race/faq-20488802

- Mitchell, T. (2020, September 25). Letter to U.S. congressional leaders. American Council on Education. https://www.acenet.edu/Documents/Letter-House-Fall-COVID-Supplemental-092520.pdf

- Molla, R. (2017, June 20). More than 60 million urban Americans don’t have access to or can’t afford broadband internet. Vox. https://www.vox.com/2017/6/20/15839626/disparity-between-urban-rural-internet-access-major-economies

- Mutikani, L. (2020, July 31). What to know about the report on America’s COVID-hit GDP. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/07/covid-19-coronavirus-usa-united-states-econamy-gdp-decline/

- New York Times. (2020a, August 30). U.S. coronavirus cases top 6 million. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/30/world/coronavirus-covid.html

- New York Times. (2020b, October 8). Tracking Covid at U.S. colleges and universities. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/covid-college-cases-tracker.html

- Office of the Governor. (2020, August 1). Seventh amended declaration of continued public health emergency and state of emergency for COVID-19. https://dehayf5mhw1h7.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/sites/594/2020/08/01035533/7th-declaration-for-covid19.pdf

- OʻReilly, T. (2005, September 30). What Is Web 2.0. https://www.oreilly.com/pub/a/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html

- OVPCC. (2020, July 9). Spring 2020 survey of faculty and students. [unpublished report].

- Parker, K., Horowitz, J. M., Brown, A., Fry, R., Cohn, D., & Igielnik, R. (2018, May 22). What unites and divides urban, suburban and rural communities. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2018/05/22/what-unites-and-divides-urban-suburban-and-rural-communities/

- Parker, K., Minkin, R., & Bennett, J. (2020, September 24). Economic fallout from COVID-19 continues to hit lower-income Americans the hardest. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2020/09/24/economic-fallout-from-covid-19-continues-to-hit-lower-income-americans-the-hardest/

- Riodan, M. (2020, September 30). The human cost of the Trump pandemic response? More than 100,000 unnecessary deaths. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. https://thebulletin.org/2020/09/the-human-cost-of-the-trump-pandemic-response-more-than-100000-unnecessary-deaths/

- Schnell, L. (2020, September 24). Some college students didn’t show up amid COVID-19, recession – especially at community college. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/education/2020/09/23/covid-college-student-enrollment-community-colleges/3511736001/

- Silver, L. (2019, February 5). Smartphone ownership is growing rapidly around the world, but not always equally.

Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2019/02/05/smartphone-ownership-is-growing-rapidly-around-the-world-but-not-always-equally/

- Smalley, A. (2020, July 27). Higher Education Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19). National Conference of State Legislatures. https://www.ncsl.org/research/education/higher-education-responses-to-coronavirus-covid-19.aspx

- Stern, K. (2020, July 8). Coronavirus Is Blowing Up America’s Higher Education System. Vanity Fair. https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2020/07/coronavirus-is-blowing-up-americas-higher-education-system

- Suzuki, K. (2020, April 16). Japanese Society 5.0 and educational technology research. TCC 2020@25 Online Conference. https://2020.tcconlineconference.org/plenary-16/

- Taglang, K. (2020, April 24). Reaction to FCC’s 2020 Broadband Deployment Report. Benton Institute for Broadband & Society. https://www.benton.org/headlines/reaction-fccs-2020-broadband-deployment-report

- TCC Hawaii. (2020, April 8). TCC 2020@25, one day in our life – free plenary sessions. TCCHawaii.org. https://tcchawaii.org/2020/04/08/tcc-202025-one-day-in-our-life-free-plenary-sessions/

- Torigoe, H. (2020, May 18). Covid-19 moving a school online. TCCHawaii.org. https://tcchawaii.org/2020/05/18/covid-19-moving-a-school-online/

- UH News. (2020a, March 12). University of Hawaiʻi actions to address COVID-19 pandemic. University of Hawai‘i News. https://www.hawaii.edu/news/2020/03/12/uh-actions-address-covid-19/

- UH News. (2020b, August 4). Update for UH employees on teleworking in August. University of Hawai‘i News. https://www.hawaii.edu/news/2020/08/04/work-from-home-in-august/

- UH News. (2020c, August 18). UH health screening check-in app now available. University of Hawai‘i News. https://www.hawaii.edu/news/2020/08/18/uh-health-app-available/

- UH News. (2020d, August 26). Important information: COVID-19. University of Hawai‘i News. https://www.hawaii.edu/emergency/important-health-information-novel-coronavirus/

- UH News. (2020e, October 15). UH stems enrollment decline despite pandemic and economic fallout. University of Hawai‘i News. https://www.hawaii.edu/news/2020/10/15/uh-enrollment-pandemic-fallout/

- UH Online Innovation Center. (n.d.). Remote instruction during an emergency. https://www.uhonline.hawaii.edu/id/preparing-to-teach-online/emergency.php

- University of Hawai‘i. (n.d.). Remote learning in fall 2020. UH Online. https://www.uhonline.hawaii.edu/emergency

- University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. (2020, September 30). COVID-19. University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. https://manoa.hawaii.edu/covid19/

- Wheeler, T. (2020, May 27). 5 steps to get the internet to all Americans. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/5-steps-to-get-the-internet-to-all-americans/

- Winslow, J. (2019, July 26). America’s digital divide. Pew Trust Magazine. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/trust/archive/summer-2019/americas-digital-divide

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). WHO covid19 data. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Retrieved October 10, 2020, from https://covid19.who.int/

Bert Y. Kimura

Professor Emeritus

University of Hawaii

Honolulu, Hawaii, USA

Kimura spends half of each year in Hawaii and half in Kobe, teaching Educational Technology at the University of Hawaii and providing guidance on new teaching methods that make full use of ICT at Kansai University.

Return to 29th JAMCO Online International Symposium contents page

Return to 29th JAMCO Online International Symposium contents page