21st JAMCO Online International Symposium

March 14 to September 15, 2013

Tsunami Response Systems and the Role of Asia's Broadcasters

[Discussant 1] Role and Tasks of the Media in Mitigating Disasters : Lessons from the Indian Ocean Tsunami

The most recent disaster resembling the March 11th earthquake was the Indian Ocean Tsunami of 2004. Two massive tsunami-generating tremors of a scale that is said to occur only once in 1,000 years shook the ocean floor only six years and three months apart. Nineteen thousand lives is a tremendous number, but without the lessons learned from the Indian Ocean Tsunami, there is no doubt that the figure would have been much higher. Japan was able to decrease the impact from tsunmi because of the lessons learnt from the 2004 disaster.(*1)

The number of dead and missing in the Indian Ocean Tsunami was as high as 230,000. We pray for the repose of their spirits. The magnitude of the earthquake, the time-lapse until the tsunami reached land, and the height of the waves were features similar to those of the Great East Japan Earthquake. In some areas it took longer for the tsunami to strike the land. The Indian Ocean quake occurred at around 8:00 a.m. (local time), so like the East Japan quake, which hit just before 3:00 p.m. (local time), it was during daylight, a time when most people were awake. The weather was clear, meaning the disaster was not compounded by a blizzard or typhoon. Despite those relatively favorable conditions, why was it able to take the lives of 230,000 people? What were some of the measures that radio, television and other media services could have adopted to mitigate the disaster?

Based on the reports submitted to this symposium from Thailand, Indonesia, and Sri Lanka, this essay looks at five reasons why the mass media did not perform roles that would have helped to reduce the toll in human lives from the tsunami, and suggests a number of issues that will have to be overcome in disaster broadcasting from now on in these regions.

(*1) As Katada (2012) has observed, Japanese children came to be taught in schools “to be wary of tsunami after an earthquake,” and they were shown images of the immense tsunami in the Indian Ocean. The children soon remembered those images when the powerful earthquake hit, driving home the importance of evacuating to high ground on their own.

Preconditions for Disaster Mitigation

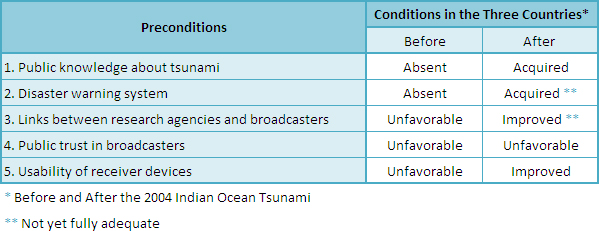

The mass media can play a major role in mitigating natural disasters, but that is only possible if a number of preconditions are fulfilled. Figure 1 shows relevant conditions for disaster mitigation and the situation in the three countries regarding each. As the figure indicates, much improvement in these preconditions—which have been largely fulfilled in Japan—can be seen after the disaster in the three countries, although the situation remains inadequate in some ways. However, the media’s presence and social mission varies from one country to another. The public’s trust in the media and density of communication between media and government agencies and research agencies differ too.

Below we will look at the situation on these five points at the time of the Indian Ocean Tsunami and later.

Public Knowledge about Tsunami

Tsunami is a natural phenomenon for which warnings and forecasts of shore-arrival time can be given in advance. Without the understanding of the way tsunami occurs and the possibilities of their rise following undersea earthquakes, neither the inhabitants living in potential disaster areas nor the mass media that serve them will be aware of the dangers. The reports submitted to this symposium by Sri Lanka and Thailand note that “99 percent of citizens do not know the difference between a high tide and a tsunami” (Asees 2013) and “[people] did not know what a tsunami was” (Nitsmer 2013). Ndolu does not make specific mention of this matter in the Indonesian report, but Hayashi (2010, 308) observes that “the last major tsunami to strike in this region was in 1907, and from that time (until the 2004 tsunami: added by author), people did not have any knowledge of tsunami.” As a result, the recognition that the waves were connected to an earthquake was initially lacking that in the inland area of Phuket, Thailand, there were rumors that “a huge flood hit the beach,” during the morning of the tsunami (Hayashi 2010, 142).

Even among people who knew that tsunami is a natural phenomenon appeared to believe the long-standing myth that “the Indian Ocean does not have tsunami.” Words for tsunami may have rarely been heard, but stories did survive from long ago about warnings of tsunami. In Sri Lanka (Asees 2013), several stories had been recorded of tsunami experienced there and Tanaka (2013, 75) reports that stories have been passed down among the Moken “sea gypsy” people of Thailand that “if the sea suddenly recedes, flee to a hill.” In fact, after the sea receded after a small first wave of the tsunami in 2004, people even went down to look at or catch the fish that were beached as the waves suddenly withdrew, having no idea whatsoever that a tsunami would soon come plummeting inland.(*2) So obviously this kind of ignorance was one major factor in the high death toll.

As a result of the occurrence of the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami and the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and the resulting tsunami disaster, people around the world with access to the mass media from 2005 onward have doubtlessly acquired some knowledge of the reasons tsunami occurred and how much damage they can do. Memory of major disasters naturally erodes with the passage of time, but the mass media, which see themselves as responsible for disaster reporting, can play the role of keeping alive and updating collective memory.

(*2) The drawback occurred at 9:30 am in Khaolak to 100 meters and in Phuket to 500–1000 meters (Nitsmer 2013). Eyewitnesses reported a drawback in the Aceh province, western coast village of Lockgar at 200 meters and in Pulau village at 2000 meters (Hayashi 2010, 237–239). The time is not clear, but a report of a person who, startled by the earthquake, left his home and went to a nearby coffee shop suggests the drawback came at least 20 minutes after the quake.

Disaster Warning Systems

Southeast Asia is a region where natural disasters—volcanic eruptions, droughts, floods, and high tides—occur frequently. The damages from these phenomena can be decreased by issuing early warnings and calls for evacuation from dangerous areas. However, Asees (2013) and Nitsmer (2013) indicate that no warning system was in place for tsunami.

After the 2004 tsunami, all the countries that suffered from the disaster established tsunami warning systems. These systems are based on the models built by the U.S. Department of Commerce-run Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC) and Japan, a country prone to tsunami.

In subsequent disasters, however, Tanaka (2013) found in his onsite survey that the systems that were set up are still inadequate in various ways. For example, on April 11, 2012, when another earthquake occurred off Aceh province in Indonesia, the Agency for Meteorology, Climatology and Geophysics (BKMG) issued earthquake and tsunami warnings throughout the country within five minutes. One of the commercial broadcasters transmitted the warning as early as 1 minute 16 seconds after it was issued by the Agency. However, some of the tsunami-warning sirens installed in the city of Aceh did not work immediately or did not make any sound at all. The failure of the system was apparently caused by both human error and mechanical breakdown (Tanaka 2013, 50–57).

In Thailand after the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami disaster, a National Disaster Warning Center was established. In August 2011, flooding began in northern Thailand and peaked during October and November. According to Tanaka’s report (2013, 61–70), the warning alarm was delayed due to the fact that the rainfall, waterway water level, and relevant other data were gathered by different government agencies and there were no agency that can put the data together and devise countermeasures. None of the authorities related to flooding, moreover, was ready to take responsibility for issuing warnings. The newly established Thai disaster center, moreover, placed priority on tsunami countermeasures that it could not fully function against flooding disaster.

Links between Research Agencies and Broadcasters

Disaster warning systems do not work independently. The media, especially the mass media, are expected to play an especially important role. The mass media is equipped with the ability to gather information from a wide range of area and report it to the public after verifying the validity of such information. If there is an agency for disaster countermeasures, the mass media can get their information promptly and transmit accurately. In the case of Sri Lanka, Asees (2013) regrets that the role the broadcasters could play in mitigating disaster at the time was very limited because there was no tsunami warning system.(*3)

Concerning the Indian Ocean Tsunami disaster, according to Nitsmer (2013), no tsunami warning had been issued as of 9:30 am local time, but the FM100 radio station had apparently obtained information on the tsunami by some means and was the first to air the event. Its broadcasting area, however, was Bangkok and its vicinity, so the word did not reach the areas hit by the waves. Channel 11, a television broadcaster based in Phuket, broadcasted the news immediately after the tsunami hit, Nitsmer reports.

Ndolu (2013) applauds the speed with which the public service radio station RRI in Indonesia went into action regarding the tsunami, that the reports were broadcasted within 24 hours after the earthquake and was the earliest among the media in Indonesia. However, it also means that there were no reports before or immediately after the tsunami’s arrival. Regarding television broadcasting on the tsunami disaster, Ndolu reports that the all-news channel Metro TV gathered news through the satellite for one month after the tsunami.(*4) Ndolu’s report looks into the role of community radio stations that developed as a result of the tsunami disaster. In contrast to the mass media, which are able to gather information from a broad area, it is still difficult for community radio stations to establish links with research institutions and obtain information necessary to mitigate disasters.

What could compensate for delays in news broadcasting is the rapid spread of personal media in various parts of Asia in recent years. In emergencies, however, as was experienced in Japan as well, congestion in transmissions can make it difficult to get a phone connection. This problem also troubled mass media’s efforts to gather information at the time of the Indian Ocean Tsunami. One of the challenges for the future is to discover the best way for the personal and mass media to share roles at such times and to guide people toward such direction.

(*3) On the other hand, sometimes liaison with the government and faithful reporting of its statements can be misleading. Tanaka (2012, 66–67) observes that at the time of the great floods in Thailand in 2011, when the state-run broadcaster NBT faithfully transmitted the official views of the government, despite the latter’s lack of reliable disaster countermeasures, ended up further undermining the reliability of the information NBT provided. By contrast, confidence in the Thai public broadcaster PBS, which was more careful about the reliability of information, increased.

(*4) Ndolu, however, is critical of the various problems of broadcasting stance resulting from the fact that Metro TV is a commercial channel.

Public Trust in Broadcasters

In Japan, the typical response when an earthquake is felt is to turn on the television and select the public service broadcaster, the NHK. Within a few moments, the screen shows the epicenter of the quake and the magnitude along with a superimposed message such as, “There is no danger of a tsunami.” In being prepared and forewarned about natural disasters in general, people in Japan are accustomed to checking weather information at least once a day and even more frequently when they live in areas where typhoons or blizzards are expected. When a severe weather condition is expected broadcasters will offer specific advice to their audiences, such as “return home as soon as possible.”

In other countries in Asia, this kind of trusting relationship between broadcasters and audiences has not yet been fostered. The mass media can function to help mitigate disasters only if broadcasters recognize their mission and execute necessary abilities to gather, analyze, and transmit information and the public become interested in media reports and become accustomed to viewing it.

As of 2004, broadcasters in Indonesia had not been designated as a provider of disaster-prevention information (government orders were issued in 2006). Even in the Disaster Prevention and Mitigation Law enacted in Thailand in 2007, the role of broadcasters was not clearly defined (Tanaka 2013, 53, 65). Under these conditions, if the mass media are to take up the mission of mitigating disaster among the people, journalists must be conscious of their responsibility to the society and the mass media needs to devote time and resources to disaster-related content. Creating information-gathering networks and cultivating analytical capabilities involves certain costs.

In Indonesia, Ndolu (2013) reports that the public radio broadcaster RRI has played an important role in disaster reporting but the audience ratings of the public television broadcaster TVRI are quite low, and their capacity for information gathering is poor (Tanaka 2013, 52–53). That being the case, it would be hoped that the all-news channel Metro TV or other leading channel, TVONE might take the lead in disaster reporting. However, as commercial stations, they have their limitations. In Thailand, while there is a state-run broadcaster, the public broadcaster PBS appears to be more aware of its role vis-à-vis the public, as reported by Tanaka (2013, 65).

Unfortunately, even if the mass media manage to provide early warnings, it does not guarantee that people will promptly evacuate from danger zones. According to Oishi (2006, 33), even if the sender of information broadcasts messages with a clear intention to the receiver, that message does not necessarily change the views, attitudes, or behavior of the receiver who comes into contact with it—this is known as a problem of persuasion in the field of social psychology. Oishi also introduces the communications theory of Paul Lazarsfeld and Elihu Katz concerning how concepts flow from mass media to opinion leaders and then to the opinion leaders’ followers.

In fact, according to Tanaka (2013, 60), at the time of the volcanic eruption on the island of Java, Indonesia, in 2007, many inhabitants who believed the reassurances given by the so-called “guardians” of the volcano and did not evacuate became victims. Also, according to Tanaka (2013, 57), at the time of the Aceh earthquake in 2012, 50 percent of the routes by which people obtained information that stimulated them to evacuate was neighbors, whereas television and radio was only 11 percent, lower than that of tsunami siren (15-20 percent) and almost equal to telephone and SMS (10 percent). Switching on the TV to obtain information “whenever something happens” is a practice in Japan that is yet to be shared in these countries.

Usability of Receiver Devices

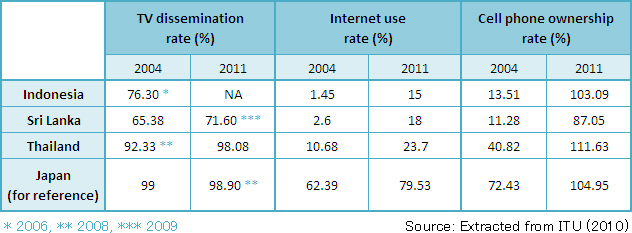

Another possibility for disaster mitigation is the use of wireless receiver equipment. According to the Yearbook of Statistics: Telecommunication/ICT Indicators 2002-2011, the television dissemination rate is not 100 percent in the countries as they are shown in Figure 2. Alternative sources for obtaining information include the Internet, cell phones, and radios. Figure 2 shows that Internet use is more limited than television use; cell phone ownership was quite low as of 2004 but sharply increased after that.(*5) As observed above, the effective combination of mass media and personal media is expected to be helpful for disaster mitigation.

Considering the fact that electrical power supply is often not stable in these regions, people may not always be in the condition to watch television.(*6) Besides, power outages often occur when a major tsunami hits.

In that sense, radios seem ideal as certain types of radio can function with hand-driven power in case electricity or batteries are not available and they are inexpensive as well. We hope that the usefulness of radios will receive renewed attention as an effective means for both sending and receiving information about disasters. It may be necessary for the radio broadcasts to become trustworthy and the people to become accustomed to listening to it. Today, when radio use is declining with the spread of personal media, getting people to listen to radio more frequently is a difficult yet important challenge.

(*5) The ITU statistics do not include data for dissemination of radios.

(*6) It is probably fair to consider that the rate of ownership of televisions in poor villages along the coat is even lower than the national average. For example, according to the survey conducted in fishing areas along the eastern coast of the island of Panai in the Philippines in 2004 (Yamao 2006; this report’s author participated), ownership of television was 56.2 percent, refrigerators was 21.3 percent, and “have but broken” was a frequent answer.

REFERENCES

- Asees, Mohamed Shareef (2013). Tsunami Disaster Prevention in Sri Lanka, The 21st JAMCO Online Symposium, https://www.jamco.or.jp/en/symposium.

- Frederik, Ndolu (2013). The Roles of Broadcasters in Disaster Reportage; A Lesson Learned from Tsumani Repotage in Indonesia, The 21st JAMCO Online Symposium, https://www.jamco.or.jp/en/symposium.

- Hayashi Isao ed. (2010). Shizen saigai to fukko shien (Minpaku Jissen Jinruigaku Shirizu 9) [Natural Disasters and Reconstruction Support (Minpaku Practical Anthropology Series 9)], Akashi Shoten, 2010.

- International Telecommunication Union (ITU 2012). Yearbook of Statistics: Telecommunication/ICT Indicators 2002-2011, ITU, 2012.

- Katada Toshitaka, NHK News Crew, and Kamaishi Municipal Board of Education, (2012). Minna o mamoru inochi no jugyo: Otsunami to Kamaishi no kodomo-tachi [Classes on How to Keep Everyone Safe: Massive Tsunami and the Children of Kamaishi], NHK Shuppan, 2012.

- Nitsmer, Supanee (2013). Tsunami Disaster Prevention and the Roles of Media in Thailand, The 21st JAMCO Online Symposium, https://www.jamco.or.jp/en/symposium.

- Oishi Yutaka (2006). Komyunikeshon kenkyu: Shakai no naka no media (dai 2 han) [A Study of Communication: The Media in Society (Second Edition)], Keio University Press, 2006.

- Tanaka Takanobu (2013). “Saigai hodo to kokusai kyoryoku: Ajia ni okeru bosai/gensai bun’ya no kokusai kyoryoku to hosokyoku no yakuwari” [Disaster Reporting and International Cooperation: International Cooperation and the Broadcasters’ Role in Disaster Prevention and Mitigation in Asia], NHK Broadcasting Culture Research Institute’s Nenpo, 2013, No. 57, pp. 41-85.

- Yamao Masahiro, ed. (2006). “Progress Report on the Survey in the Banate Bay Area,” No. 1 (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research Report), 2006.

Haruko Yamashita

Professor, Faculty of Economics, Daito Bunka University

Born in Japan in 1957, she obtained Bachelor's degree in Economics from Doshisha University, Master's degree in Economics from The University of Chicago and Doctoral degree from Hiroshima University.

Her academic career started in 1995 as an Assistant Professor, then became Associate Professor and Professor of Meikai University. She took her current position in April 2013.

Focusing on the studies of the broadcasting and fishery industries, she recently authored Sakana no Keizaigaku (Dai 2-han) [Essays on Fishery Economics (second edition)], Nihon Hyoronsha publishing, in 2012 and contributed a chapter to Minoru Sugaya (ed.) Telecommunication Policy and International Cooperation in Asia Pacific Region titled as International Relation in Asia-Pacific Waters: Fishery as a Main Industry, Keio University Press, 2013.

Return to 21st JAMCO Online International Symposium contents page

Return to 21st JAMCO Online International Symposium contents page